Behind-The-Scenes Story of CCPM

This article is a digest of the beginning of "The Critical Chain Implementation Handbook" (Createspace, 2014) with permission of David Updegrove, the author.

In 1986, representatives from the Norwegian energy company Statoil approached Dr. Eli Goldratt with a proposal. As builders of North Sea oil rigs, the people at Statoil had by necessity become project management experts. Yet in spite of this expertise, they still had great difficulty in completing their projects on time. They told Goldratt that to really determine the duration of a project, they would multiply the planned duration of the project by 4 and pray.

The problem, they told him, was that their prayers weren’t answered.

Statoil’s representatives had read The Goal, and were convinced that if anyone could figure out a solution for project management, it would be Eli Goldratt. They gave him two small booklets containing, they said, everything they knew about project management. Goldratt learned that lead time was the key for projects, and that lead time was determined by the Critical Path, a concept first pioneered in the late 1950s. Additionally, he learned that in one of their projects – originally comprised of 40,000 tasks – the Critical Path actually only totaled about 40 tasks, or 1/10th of 1% of the project. The idea that the overall duration of a project is determined by a very small number of tasks captured his attention, and he agreed to work on the problem.

Two weeks later Goldratt boarded an airplane for Oslo. Unfortunately, in spite of the fact he had come to these understandings, he had yet to construct a solution.

"What would I tell Statoil?"

He started going over the situation in his head once again. His thought process went something like this:

- Critical path provides companies with a fantastic ability to focus. Nevertheless they are chronically late, even when they multiply by 4 and pray!

- These are not stupid people, and Statoil in particular is the best in the world at projects! Their estimates must be, on average, good enough… How could it be that multiplying by such a large factor still does not provide enough time?

- There must be a fundamental assumption that is missed, which is devouring the time…

- The duration of a project is the sum of the duration of the tasks along its critical path…

- But the actual duration of any task varies – often quite significantly – from the estimate…

- When a task on the critical path takes longer than its estimate, the whole project takes longer…

- But when a task on the critical path takes less time than its estimate, the project should be shorter. But this is apparently not happening! Why?

- Show me how you’ll measure me, and I’ll show you how I’ll behave…

- If estimated task durations tend to become committed task durations, peoples’ estimates will be inflated to contain enough “safety”…

- If I am a task manager, since I have lots of safety and there are other urgent tasks, I can afford to start later…

- If things magically go well and I finish early and report I’m done, I’ll lose my safety for next time, when things might not go so well. So I’d better not report an early finish…

- If I as a task manager have nothing else to do, and if being idle is frowned upon, I need to look busy—so I’ll pace myself to make sure I don’t finish early…

- This explains why only delays accumulate…

- And in projects there are many dependencies and variables… so these behaviors happen over and over again…

As the plane neared Oslo, the answer came to him—the first major premise of Critical Chain:

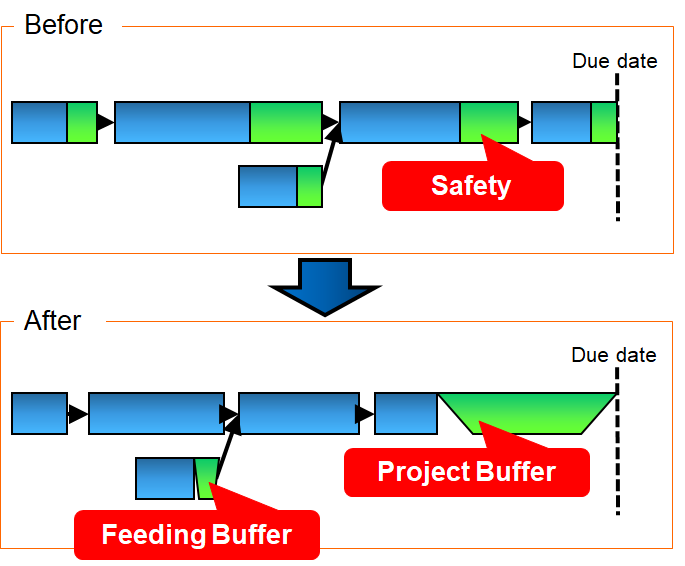

Remove safety from tasks and aggregate the safety into a project buffer and feeding buffers! Use the safety only when you need it!

Over the next eleven years, Goldratt expanded on, tested and refined his solution. By 1997 it was mature enough to be given its own name and be put into the public domain. He published the book, Critical Chain, which was a business novel like The Goal and It’s Not Luck.

During the early years of Critical Chain, it was clear that we had found a better way to deliver isolated projects on time. There still

remained the question of how to deliver all of them on time—on budget—and with their full, originally intended scope. What were the significant differences between single projects and multiple projects? As usual, Dr. Goldratt was already far ahead of the rest of us and had been testing the multi-project solution for a number of years.

Today the multi-project solution has been used to improve performance in new product development, software development, engineering-to-order, major assembly production, MRO (Maintenance, Repair & Overhaul), and many other environments in hundreds of implementations around the world.